This week I went for an early morning swim, with swifts swooping overhead, and the sound of waves crashing on the beach. Just beyond the hedge, a bamboo pole lay high up on the sand, dropped at the tide’s highest point, and darkened by its time in the water. After a little look out to sea, I stepped into the pool and settled into the routine of my swim. I was aiming for 20 minutes, as someone on the island told me 20 minutes is when it shifts from relaxation to exercise, presumably because the aerobic system kicks in. I haven’t noticed it being especially windy, but there have been quite a lot of bits in the pool recently. As I result, fragments of leaf and petals bobbed past me as I swum.

Something different caught my eye, and I saw a bee struggling on the surface of the water. I stopped, trying to scoop it up in my hands, but the water sloshed around too much for me to capture it. I carried on swimming, but my mind returned to the plight of the bee and its suffering. The next time I came close, I stopped again and looked up over the edge of the pool for a suitable aid. A long narrow leaf lay on the side. It wasn’t close enough to be able to reach for it, so I pulled myself up out of the water, went over to fetch it, and dropped back into the water to find the bee again. The leaf proved to be a useful tool, and I was able to scoop the bee out of the water, and walk with it to the poolside. There I gently tipped the leaf, and the water drained from the deep ridge without dislodging the bee. Its long back legs seemed to fight against the air. Legs too long, like a new-born foal attempting to stand up for the first time. I gently nudged the bee from the leaf, releasing it from the droplet in which it was trapped. It continued to flail its legs, and there wasn’t anything more to be done. I dropped my body back into the water and continued my swim, leaving the bee to recover, I hoped.

Thoughts flowing like water

The rhythmic action of swimming allows my mind to quietly process things, and thoughts often flow easily, like water in a stream. I can watch these thoughts without attaching to them, as if they have less weight in the water, like my body seems to! My mind briefly wondered about the plight of the bees here in the Caribbean and whether they are subject to the same threats as those in the UK. Then it flowed to thoughts about compassion. The idea of writing a Substack article about the bees as a way in to compassion started to develop.

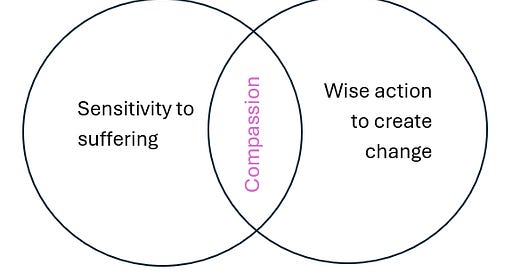

For those of you who have been subscribers for a while, you may remember that I have written a little about compassion, and Compassion Focussed Therapy (CFT) before. Compassion is not just the feeling of sadness, concern, or agape in witnessing the plight of others, but also in taking wise action to alleviate suffering.

Dr Chris Irons, Clinical Psychologist and Director of Balanced Minds, cites the following definition-

‘a sensitivity to the suffering of self and others, with a commitment to relieve and prevent it’.

He emphasises that compassion is not just an emotion, but more critically a motive to action. Compassion is an active, not a passive, or weak force. It combines our sensitivity to our vulnerability, and wise use of our power.

Compassionate acts

When we see something that pulls at our compassion, something needing our help and needing our attention, how often do we act on this? Are we willing to slow down, change course, stop, and attend to the suffering of something else, especially if we are pursuing a goal (my target of swimming for 20 minutes, for example)? Is the bee important enough for us to bother with?

This is a question that taps into the values that we prioritise in life. I was motivated to take care of the bee due to my concern for its suffering, and my desire to put an end to it.

Our motivations likely depend on our beliefs too, especially when there is a potential cost to us in taking action, and no obvious immediate reward or positive outcome for us. For instance, do we believe that nothing is separate, and all life is interconnected? This is a challenging concept when we are familiar with individualistic stories, but how might it impact on our willingness to stop to help? How does it impact on our compassion? I think it makes it more likely that we put ourselves out to help.

Of course, it could also be argued that I was seeking to end my discomfort at seeing the bee in distress, so perhaps my actions included an element of self compassion! I vaguely recall an undergraduate lecture questioning the idea of altruism. If we feel good when we help other people, is this really altruistic, or are we simply meeting our own needs to feel good about ourselves!? How psychologically healthy is it when helping has become a need, rather than a choice? Is this wise action and true compassion? These questions are interesting thought experiments, but can also have clinical implications in the therapy room.

They’re dropping like flies

As I continued my swim, my attention was drawn back to the water again. I spotted another dark shape and as I got closer, I saw a second bee in difficulty. This one was less active, and I wondered if it was moving purely due to the movement of the water. I returned to the leaf on the poolside, picked it up again, took it to the second bee and repeated the action of scooping it up, and gently tilted it onto the poolside. This bee ended up upside down and motionless. I gently righted it, removing it from the last droplet of water caught on its legs. I watched for signs of movement, relieved to see it move a little. I had done all I could, and I resumed my swim. I wanted that 20 minutes!

Picture of the rescued bee

https://camanimals.com/insect suggests it might be the western honey bee (Apis mellifera)

There is something meditative about swimming around and around, waves crashing as the sound track. As my watch showed I was getting closer to 10, then 15 minutes, the bee plight put me in mind of one of my favourite books, The Secret Life of Bees by Sue Monk Kidd. If you haven’t read this book, or seen the film, I highly recommend it. It is one of those stories that translates well to film. There is much wisdom in the book, and a couple of lines stuck with me. One, spoken about August, the head of the household, and compassionate life teacher-

“Nobody around here had ever seen a lady beekeeper till her. She liked to tell everybody that women made the best beekeepers, 'cause they have a special ability built into them to love creatures that sting. It comes from years of loving children and husbands.”

― Sue Monk Kidd, quote from The Secret Life of Bees

Compassion sometimes results in pain when we try to help others. I found a leaf to help the first bee because I thought it might’ve stung me when I put my hands out to help, not because it was vicious, but because it was threatened. It was drowning, and doing its best to stay afloat. Anything that prodded it, or upset the balance it had on that water might be considered a threat, and receive a sting. The same thing can happen when we reach out to people with compassion. We need wise ways of helping, so we do not get stung, or drown with them.

Your relationship with compassion

Compassion focussed therapy understands compassion to move in three different directions, or flows.

Professor Paul Gilbert’s Three flows of compassion- from www.nicabh.com

The three flows are-

Compassion from self to others

Compassion from others to self

Compassion from self to self

We each have a different relationship with each of these flows, some of which we may experience easily, and others might be difficult, or entirely absent. It is helpful to have a balance of the three flows.

Take a moment to ask yourself which of these flows of compassion you recognise.

Consider your relationship with these flows of compassion.

Do you find some easier than others?

Some people find it easy to accept compassion, whilst others find this difficult, and find themselves mostly operating from a place of offering compassion to others. Many people find that it is easier to be compassionate to someone else, like a friend or family, than to themselves.

A classic question in therapy is ‘What would you say to a good friend?’

This question can help generate compassionate responses that you might never say to yourself otherwise. We would never dream of treating our loved ones the way that we can sometimes talk to ourselves. When we genuinely care about a person, and want them to feel happy, we do our best to communicate that through our words and actions. It is a skill to find the right words and actions for different people!

Our cultural, social and personal conditioning of course play a part, and can be helpful to consider.

What stops you from accepting compassion and care when it is offered?

And what does it feel like when the roles are reversed? When you offer compassion to someone else, and it is brushed off or rejected?

We generally like to show others that we care about them, and to have them feel our love and concern, but these things are not givens. Sometimes compassion is blocked, or absent. For example, if we have not consistently experienced compassion from others, we might find it harder to show compassion to others, and ourselves. Or we might feel deep compassion for someone but find ourselves helpless to do anything to alleviate it, so compassion gets blocked, and over time we might emotionally cut off from it. Our sensitivity to distress, without being able to alleviate suffering, can contribute to burnout and / or depression. Wise action requires us to manage our expectations of the scale and pace of change, and to find peace in the acceptance of our limitations.

What is the wise action?

I was chewing over some of these ideas when I came upon a third shape in the water. Another bee! I repeated the rescue effort, and there were now three bees recovering in different spots around the pool. I was glad that I had helped them, but why were they falling in the pool? I couldn’t put this question out of my mind. I wanted to prevent the bees falling into the pool, rather than continuing to scoop them out.

Desmond Tutu, South African Bishop and antiapartheid activist encouraged this-

“There comes a point where we need to stop just pulling people out of the river. We need to go upstream and find out why they’re falling in.

You might consider that my job as a Clinical Psychologist is to help scoop people up when they are drowning, like with the bees. You are partially right, but I wholeheartedly believe that all psychologists also need to be answering Desmond Tutu’s call to a different type of compassionate action, and finding ways to prevent the bees from falling in the pool in the first place. This has often been my desire whilst working in psychological services and will be my tendency in my new role, I am sure. This is of course much harder to achieve, but potentially has much larger effects, if we can find the wise course of action.

Contemplating this, I was distracted by another swimmer getting into the pool- I thought to warn her about the bees around the poolside, but instead got out and moved the nearest one closer to the shaded grass. I didn’t want it to get trodden on before it had dried out enough to fly away, or for the heat of the sun to kill it off!

I don’t have the answers, but I am following the path of compassion, with sensitivity to suffering and wise action. Doing my best to get the right balance between finding this for myself and others.

“I hadn't been out to the hives before, so to start off she gave me a lesson in what she called 'bee yard etiquette'. She reminded me that the world was really one bee yard, and the same rules work fine in both places. Don't be afraid, as no life-loving bee wants to sting you. Still, don't be an idiot; wear long sleeves and pants. Don't swat. Don't even think about swatting. If you feel angry, whistle. Anger agitates while whistling melts a bee's temper. Act like you know what you're doing, even if you don't. Above all, send the bees love. Every little thing wants to be loved.”

― Sue Monk Kidd, quote from The Secret Life of Bees

Sometimes we are the bee, in need of compassion, and sometimes we are the swimmer ready to offer it. Sometimes we might choose to swim on past, lacking the time or energy to do anything about it. Try to look out for the three flows of compassion today, and notice which you feel most and least comfortable with.

Every little thing needs love, especially the bee parts of ourselves. If we are lucky, hands will continue to scoop us out of the water when we need them, at least until we can figure out how to prevent each other from falling in to start with.

“Do your little bit of good where you are; it’s those little bits of good put together that overwhelm the world.”

Desmond Tutu, Up The River

In case you are wondering, when I checked on the fate of the bees later in the evening, only one remained lying on the poolside. Saving two out of three isn’t bad.

Beautiful Jo. Compassion feels so central to all the work we do as psychologists, and feels to me like the primary medicine needed in the world today 💙

Beautiful 🙏💛🙏 In Buddhism, we aspire to practice the 'Four Immeasurables' for all sentient beings including ourselves - loving-kindness, compassion, rejoicing and equanimity 🙏💛🙏